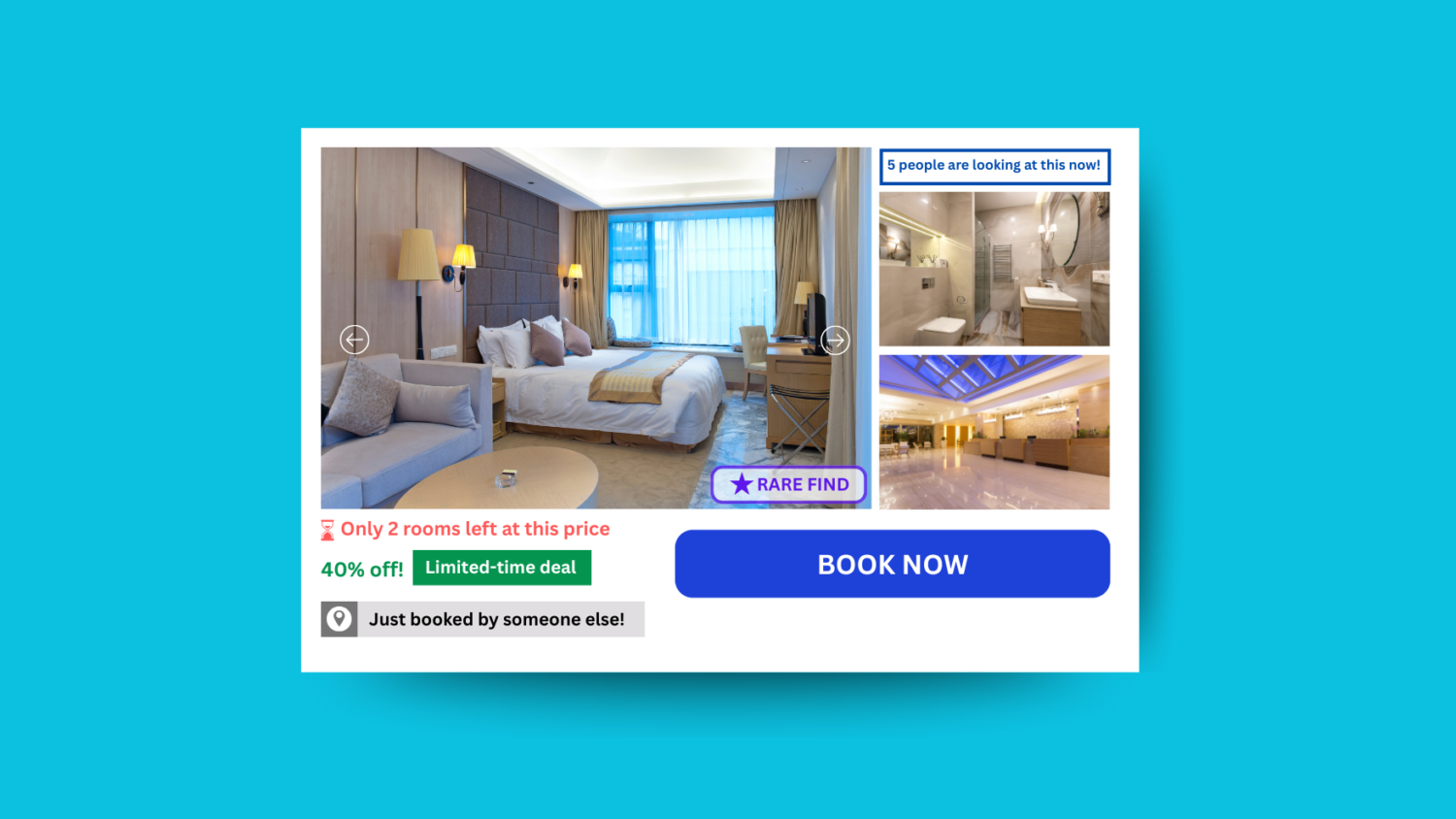

If, like many of us, you enjoyed a no-fly, UK holiday in the last year and a half, chances are you’ll have come up against some behavioural science in the booking process. Holiday sites like Expedia and booking.com are rife with ‘nudges’ (or perhaps ‘sludges’) that instil a sense of urgency, encouraging you to book more hastily than you might have otherwise. Scarcity effect is the name we give to the cognitive bias that means we place a higher value on things that are in short supply, rather than those that are available in abundance. If others are rushing to buy a product or book a hotel, we think they must know something we don’t. It’s the ‘forbidden fruit’ of biases: we want what we can’t have. The theory assumes, of course, that the thing in question is in short supply because other people want it too, rather than because it’s simply uncommon.

With the exception of this newsletter, we don’t toot our own horn too much, but as it happens, we’re gearing up for a hectic few months at Behaviour Change. We’re embarking on a range of exciting new projects, including work on a 9 year Net Zero strategy for a borough council; expanding engagement with museums and galleries, badly hit by the pandemic; delivering a new behavioural training course; and implementing another series of littering pilots in London and Birmingham. So, be quick — only 3 meeting slots left! Other clients loved us! Five other organisations like you are thinking about behaviour change right now!

Scarcity effect has become increasingly well known in marketing, along with a host of other behavioural tools and tactics: the Behavioral Scientist has catalogued some you’ll find in widespread use in the travel industry and beyond. ‘Friction’, for example, is the name we give to small steps that make a process harder or more time-consuming: you’ll find it when you try and cancel your Amazon Prime subscription, or claim a refund for train tickets. Given that we work purely on for-good projects, it’s concerning to see behavioural tools deployed more often by commercial organisations for ends which are clearly manipulative, for monetary gain or, at the very least, purely tactical. And given that ‘for-good’, to us, often means helping people adopt more sustainable lifestyles, seeing behavioural tools used to nudge people to buy stuff they probably don’t need is understandably frustrating.

That said, as modern consumers we’re increasingly adept at dodging an onslaught of advertising competing for space around us, whether that’s in physical or digital environments. So what we really want to know is: as people become wiser to the behavioural tools around them, will the effectiveness of those tools decrease? Psychology is hard to study because humans change their behaviour under testing conditions. It’s plausible that we’ll adjust our behaviour under an overload of behavioural tools too.

Share

RELATED ARTICLES

Behavioural science

What my bangles taught me about changing behaviour

Honica reflects on the behavioural learnings from wearing her wedding bangles for 40 days

09/07/25

Read moreSustainability

What AI and climate change have in common

The unsettling parallels between AI and climate change (and how to stop history repeating itself)

23/04/25

Read moreBehavioural science

The psychology of switching energy suppliers: what holds us back?

With the rise of the Energy Price Cap, Polly looks at the psychology behind switching energy suppliers

06/03/25

Read more