The biggest behaviour change experiment in living memory has unfolded before our eyes. While we at Behaviour Change haven’t been working on the Covid-19 response directly (apart from publishing these handwashing materials for employers) we have, as practitioners, been watching the situation develop with great interest.

It's been fascinating to see how elements of our personal and collective responses have supported some of the fundamental principles we work to. Behavioural theory is based on observations about the way we think, act, and make decisions in the real world — it aims to provide a realistic, evidence-based picture of human behaviour. A core concept is that we’re often ‘irrational’, or use mental shortcuts and biases to make decisions. We’re also hugely social beings, defined to a great extent by our conditioning, surroundings and the norms we’ve picked up. And, when it comes to communication, which has played a huge role in the Covid-19 response, we’re not only influenced by what people say, but who the message comes from and how it is delivered.

Over the last four months, we’ve seen a myriad of ways in which people have behaved irrationally or responded in self-contradictory ways to lockdown restrictions. It should be noted that in behavioural terms, ‘irrational’ doesn’t necessarily mean we’re being foolish. We might simply be defaulting to mental shortcuts or biases we’ve picked up through life, or be reflecting a lack of access to, or ability to interpret, reliable evidence.

Take the example from our last article, when we touched on the effectiveness of some salient measures like floor markings for queuing outside shops. But we also noted that, seemingly nonsensically, distancing often totally breaks down once you’re inside the shop, despite evidence that you’re more likely to transmit coronavirus inside.

Throughout the pandemic, many government decisions have been condemned as ‘irrational’, too. Take the 14-day self-quarantine for international arrivals at UK airports, which the government finally introduced around two months after the peak, and long after allowing arrivals from virus hotspots to import Covid-19 1,300 separate times. There has been widespread popular support for international quarantine, which, again, may have all sorts of social, political and scientific explanations. This continues even though the evidence would suggest that the UK is more likely to be sending the virus out around the world than receiving it from elsewhere and that this is the point in time at which introducing quarantine arguably makes the least sense.

Many situations we’ve encountered in our personal networks and through the news over the last few months have led us to speculate that there are interesting gaps between what we perceive the risks to be vs. what the risks actually are. So, some may oppose schools returning, but be happy to attend a kids party against lockdown rules. I’m sure we’ve all heard about this or that person who’s hosted a barbecue or gone home with their date. It’s as though we all have our pet peeves about how others are breaking the rules, while we at the same time find excuses for other types of infractions. Perhaps we’re all making our own individual calculations of risk, with only passing reference to facts or data? Emotion, and our own personal preferences and desires, clearly play a role in determining our interpretation of the rules. While we have no intention of defending Dominic Cummings’s day trip to Barnard Castle — to which we’ll come back later, on the theme of leaders and ‘messengers’ — I’m sure we all know of people in our personal lives who’ve made similar mistakes: calculating their own version of the rules based on a subjective perception of ‘risk’ (though they probably weren’t advising the government on the lockdown rules…).

We're social creatures

It's well evidenced in behavioural theory that we’re strongly influenced by others, which leads to social norms developing in groups or societies. One way we’ve seen this at play in the last three months has been in the weekly clap for the NHS and carers — stepping out of the front door at 8pm on Thursdays to bash pots and pans became a weekly ritual. While this started as a show of sincere respect and appreciation for front line workers, drawing tears of emotion from many, it quickly developed a strong normative element.

Social norms create pressure and expectation which can then be weaponised against those who aren’t seen to be taking part. Perhaps this was especially true in areas where people know their neighbours and there was a sense of accountability in turning out for the clap. Epitomising the darker side of social norms is the story of this woman, who was “named and shamed” by her neighbours on Facebook for missing the clap because she fell asleep. Afterwards, she said she felt like a “total outcast on a previously friendly street” — a perfect summary of the danger of prescriptive social norms.

On the other hand, one area where social norms could be used for a really positive effect is in the wearing of face coverings. This is now compulsory on public transport, but even though this new rule came into effect last Monday, and was well publicised in advance, a “sizeable minority” ignored it completely. While there may be many factors playing into this, like the availability of masks or a lack of planning, we’re curious about the role of social norms. In some Asian countries, for example, there’s a pre-existing shared understanding that wearing a mask is for the benefit of others, not just yourself. In the UK, where masks are largely new and we haven’t yet established the same collective consciousness, do people feel silly, awkward, or even uptight by abiding by a rule which is visibly ignored by many? If we want to encourage uptake of face coverings, framing them in ways which establish a positive social norm could be helpful — take a look at this example of positive framing we came across on Twitter.

We're creatures of habit

As the saying goes, we’re creatures of habit, with much of our behaviour coded in advance by the context we’re in, and therefore resistant to change. It’s easier to make changes when our usual habits or contexts are disrupted — whether by a last-minute delayed train or a big life moment, like moving house or becoming a parent. The pandemic is one huge exogenous shock, a shared moment of change we’re all living through.

A great example of how we’ve been forced into new habits is in the transition to remote working, with around 50% of the UK population now estimated to be working remotely compared to 5% last year. Arguments for the benefits of remote working have been around for a long time, from saved time to reduced emissions and improved accessibility. Nonetheless, it took the shock of Covid-19 to disrupt the default of in-person working and encourage us to access technology which already existed. In some cases, a culture change was needed too: the narrative about working from home was previously one of relaxation or ‘skiving’. Now a new narrative about remote working can draw on improved mental and physical wellbeing, escaping a punishing commute, having more time with family and establishing climate-friendly lifestyles.

At Behaviour Change, much of our work is in sustainability, and we all know by now that responding to the existential threat of climate change will require profound transformations of our lifestyles and behaviours. Research from the Committee on Climate Change estimates that 62% of emission reductions will require some form of behaviour change. We’ve been thinking hard about how we can best use this experience as a springboard into a new normal where pro-environmental options are the default. Just look at the way people have dusted off their bikes during lockdown. It’s essential that we take this global moment of change to build back better.

We're strongly influenced by who messages come from and how they're delivered

From the very beginning, communication and messaging have had a huge role to play in the UK pandemic response. Among the Behaviour Change team, we had varying opinions on the three-stage ‘Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives’ message — but we all agreed it was significantly clearer than the ‘Stay Alert’ announcement introduced in May and the speech which accompanied it. ‘Stay Alert’ offered a distinct lack of clarity at what still felt like a relatively early and delicate stage in the pandemic response. In our work, we always try to be as clear as possible when it comes to defining the behaviour we’re focusing on, because many of the objectives we might want to achieve in a project or campaign aren’t actually behaviours in themselves. Unlike ‘staying home’, ‘staying alert’ isn’t a behaviour and is even more open to interpretation. Compare it to specific messaging like ‘wash your hands’, ‘avoid large gatherings’, or ‘wear a mask on public transport’.

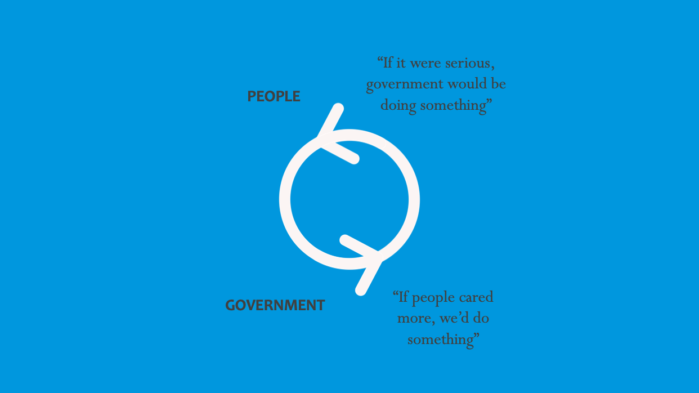

When it comes to communications, ‘messengers’ also have a large role to play. Behavioural evidence shows that when we trust or relate to the person or organisation delivering a message, we’re more likely to act on their advice. One wonders if the faces of the lockdown and daily briefings have been particularly relatable to large sections of the British public. There’s also some evidence that the Dominic Cummings fiasco contributed to lower compliance with lockdown rules, because of the way he, and the Prime Minister, undermined public health messaging by refusing to admit wrongdoing. A YouGov poll found that one in five people said they were following the rules less strictly in the week after the story broke than they were previously, and a third of those people cited Cummings as the reason.

Behaviour change in context

In the early days of the Covid-19 response, there were suggestions that behaviour change theory was being given too much of a role in poor decision making and ultimately being part of the problem more than the solution. We often find that people want to overstate the role that ‘nudges’ can play in changing the world. Behaviour change is bigger than nudges and is a complement to, not a replacement for, systems change, policy, and leadership. Now that lockdown is loosening, however, adapting our behaviour is increasingly important to manage Covid-19 going forward. (Check out our last piece on social distancing, handwashing, and active travel in workplaces). Inevitably, messaging instructing us as we come out of lockdown will be more complex and ambiguous than that needed as we went into lockdown, so clarity will be key.

How easy a behaviour change is to make is normally a defining factor in its success. Covid-19 has drawn attention to all sorts of inequalities existing in the UK: lockdown is harder if you live in cramped accommodation, easier with a big garden and weekly Ocado deliveries on their way — as Emily Maitlis so eloquently pointed out. Lockdown has also put the spotlight on racial inequalities, housing inequalities, the pre-existing crisis in social care, and inequalities in access to nature, as well as the nation’s reliance on key workers, who are often underpaid and unappreciated.

As we move into a less restricted phase of our response, behaviour change will be a powerful method for managing transmission. However, much more work will be required to understand the nuances of behavioural approaches and their consequences in the real world. That said, some of the fundamental principles have held true more than ever — our propensity to act on emotion over evidence, our malleable social natures and the role of clarity in communication.

Share

RELATED ARTICLES

Behavioural science

‘Hard-hitting’ campaigns alone won’t knock out rising cancer rates

Kate explores why 'raising awareness' is not enough to drive an effective behaviour change strategy

18/09/23

Read moreSustainability

Climate, Covid, and Moments of Change

How can we build back a better world after the pandemic?

16/03/21

Read more